This semester, a dedicated team of students and faculty at Bucknell University embarked on a unique interdisciplinary project that blended data science, creative writing, and ecological storytelling. Their mission was simple yet ambitious: to create interactive tools that would help writers draw inspiration from real-world ecological data.

Guided by Professor Sara Stoudt, who provided technical frameworks and mentorship, and Professor Elinam Agbo, who brought a writer’s sensibility to the work, the project bridged multiple disciplines and approaches.

The student team was led by Caitlyn Hickey, a junior majoring in Applied Mathematics with a minor in Physics, and Shaheryar Asghar, a freshman majoring in Economics and Psychology with a minor in Creative Writing. Together, they combined technical skill, creative insight, and a shared passion for making complex information accessible, meaningful, and beautiful.

Throughout the semester, the team worked collaboratively, reading, writing, coding, and revising, to design a series of R Shiny apps that would transform ecological datasets into storytelling launchpads. Created in partnership with The Dodge, a literary magazine devoted to nature writing, the project supports its writers while also weaving into a broader effort to cultivate and expand the field of eco-writing.

What follows is a behind-the-scenes look at the process, the apps, and the broader vision that shaped this project.

Foundations in Nature Writing

Before beginning app development, the team immersed themselves in the world of eco-writing. Each week, they read selections from The Dodge, analyzing how writers captured the complexities of the natural world through diverse creative styles, from landscapes like the Sundarbans and shifting islands in Piyali Mukherjee’s Death is a Name Spelled in Stripes to living beings like whitetail deer and oak trees in the recent Waiting in the Woods by Seph Murtagh. These literary explorations then served as inspiration to explore related data sets, such as tracking the changing shape of the Sundarbans, studying whitetail deer population trends, or examining the timing of oak leaf drop in late fall. In parallel, the team practiced their own eco-writing, completing freewrites based on personal observations of nature around them. With inspiration from other writers and the world around them, the team set out to find potential datasets that could lead to brand new stories.

This research revealed an essential insight: creative prompts grounded in nature must leave space for imagination. The team realized that statistical-style questions would not inspire compelling storytelling. Instead, the goal became to create open-ended, evocative prompts that would encourage writers to craft their own paths through the data. These early exercises shaped both the content of the apps and the broader philosophy behind the project.

Reflections from the Field: Voices from the Eco-Journal

As part of the early creative process, each team member kept a nature journal, capturing small observations and moments that deepened their relationship with the natural world. These entries became an essential part of shaping the apps’ design, encouraging a style of interaction that privileges patience, attention, and individual reflection. Below are selections from Shaheryar Asghar and Caitlyn Hickey, offering two different windows into this journey.

From Shaheryar Asghar’s Journal

In one of his early entries, Shaheryar writes about the persistent motion of a single red fish in the greenhouse:

“There’s a tank there, full of fish. Most of them are sluggish this time of year, drifting like forgotten thoughts. But one fish, a red one, never stops moving. I’ve gone at different times—midday, dusk, and even once at night, when the only light came from my phone screen. Always, the red fish is in motion, tracing the same restless pattern along the glass.”

Over time, what once seemed frantic took on a new quality:

“I watched for minutes that stretched into something longer. Did it sleep? Did it tire? It never faltered, never slowed. I left before it did.”

Yet weeks later, when Shaheryar returned to observe again, he noticed a shift:

“The fish seemed slower—its movements more deliberate, less desperate. It no longer moved with the same relentless urgency.”

Sharing this observation with a friend, he wrote:

“They shrugged and said, ‘It still looks pretty fast to me.’ That moment stayed with me. The change I saw was not necessarily in the fish. It was in me.”

Through this interaction with the red fish, Shaheryar reflected on how attention shapes perception, a lesson that deeply informed the philosophy behind the apps: creating spaces where users’ own ways of noticing could unfold, without forcing a singular path or pace.

From Caitlyn Hickey’s Journal

Caitlyn’s entries offered a different kind of noticing, grounded in familiarity and small moments of hope. Reflecting on a long-standing habit, Caitlyn writes:

“Since elementary school, I have had one weird talent: finding four-leaf clovers. Every time I walk to class, I can’t help but stare at the ground and look for clover patches. Sometimes I pick them and press them in my phone case. Other times I leave the patch alone so others can find them.”

This gentle practice of attention persisted even through disappointment:

“With the snow finally melting this week, I found my eyes scanning the patches of grass starting to poke through. The grass wasn’t as green as I remembered. The blades had been cemented down by the weight of the snow… Unfortunately, there were no signs of clovers.”

Yet rather than frustration, Caitlyn captures a hopeful patience:

“Maybe the seeds will sprout farther down the path. Maybe the patch will come back larger or not return at all. Only time will tell.”

These reflections reveal how observation isn’t only about immediate discovery; it’s about trusting in rhythms of return, change, and unseen growth—a sensibility that shaped how the apps leave space for curiosity and gentle exploration.

Together, these journal experiences shaped the project’s approach: crafting apps that do not dictate meaning but instead open landscapes for each user to notice, reflect, and interpret in their own time.

Building the Apps

Each app developed through this project offers a distinct portal into ecological storytelling:

1. National Parks App

Shaheryar Asghar led the development of the National Parks App, designing an interactive platform that allows users to explore biodiversity across America’s national parks through flexible filtering and comparative analysis.

Using verified datasets compiled by the National Park Service, the app catalogs a wide range of plant and animal species observed in different park ecosystems. Users can filter species by location and category—plants, mammals, birds, reptiles, insects, and more—gaining an intuitive sense of how life is distributed across varied landscapes, from deserts to forests.

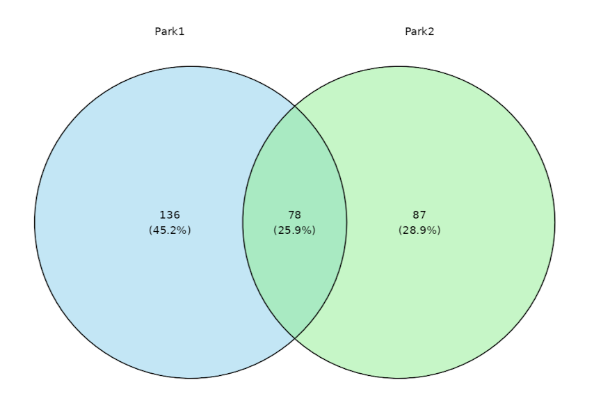

As users apply filters, visual summaries update automatically to reflect their selections, helping them navigate species diversity both broadly and in detail. Shaheryar also developed a comparative feature: an interactive Venn diagram that highlights species shared between parks, species unique to particular parks, and species listed as endangered. This functionality offers deeper insight into ecological patterns, making it easier to observe both the richness and vulnerability of different environments.A dropdown table includes both common and scientific names, making it easier for writers to dive deeper into their research.

The National Parks App invites writers to go beyond listing species, offering a foundation for stories about conservation, biodiversity, adaptation, and the delicate threads that tie ecosystems together.

2. Great White Shark App

Caitlyn Hickey led the development of the Great White Shark App, curating and processing verified sightings data from iNaturalist to visualize how great white sharks have been observed across different times and locations.

Caitlyn carefully filtered the observations for accuracy, selecting key fields such as date, time, latitude, longitude, and user agreement rates to ensure the integrity of the dataset. The sightings were then organized into decade-based groupings, with distinct colors and point shapes assigned to each era. This structure allows users to explore how observation patterns have shifted across decades and identify hotspots of shark activity.

Caitlyn also designed the temporal filtering system and interactive mapping layers, ensuring that users could move smoothly through the spatial and historical dimensions of the data.

The Great White Shark App offers writers a new way to imagine marine life, inspiring narratives about environment, presence, human interaction with nature, and the silent patterns hidden within the ocean’s depths.

3. Deer App

The Deer App visualizes the tracked paths of a deer pair over time, allowing users to explore how the animals move in relation to one another, when they are most active, and how their behaviors shift across the days of a week. Rather than presenting static data points, the app invites users to follow a living narrative of motion, habit, and patterns of behavior.

This app was developed by Professor Sara Stoudt as a prototype to demonstrate how ecological data could be used as a foundation for creative storytelling. Her early work on mapping deer movements provided an essential starting point for the broader project, offering an example of how nature’s rhythms can be translated into interactive, inspiring formats for writers.

Crafting Data-Driven Prompts

During the weeks of heavy app development, the prompts fell to the wayside. Being in the weeds of debugging and coding meant each of us could not see the bigger picture in our data sets. Once the early app was up and running, we focused our efforts on finding the stories in these data sets. Shaheryar challenged us to

“Scan the animals observed at a national park that captured our attention.”

Then, to think critically about

“a species you didn’t expect, a pattern in the numbers, or perhaps the lack of sightings?”

Caitlyn took a different approach and brough fiction into the picture by encouraging us to

“Write a legend around one of these hotspots that explains why this spot has attracted great whites across decades. What would the legend be from the shark’s perspective? The nearby humans?”

Along the way, they also took time to reflect on one another’s prompts, putting themselves in the writers’ place to imagine how the journey would unfold from their point of view. Working together, they refined each prompt so that it didn’t just ask for an answer but invited curiosity and exploration.

They continued to draft dozens of prompts throughout the semester where the ones beloved by the team found their way onto the apps. Slowly, updates to the app and prompt collection began to happen simultaneously as the final iteration took shape.

A Collaborative Process

The work was highly collaborative at every stage. Professor Stoudt’s technical guidance helped the team turn rough prototypes into polished, functioning apps. Professor Agbo helped ensure that the prompts and framing stayed grounded in the traditions of creative writing. Caitlyn’s technical acumen and attention to detail strengthened the integrity of the datasets and visualizations. Shaheryar’s creative instincts helped refine the apps’ user experiences and narrative framing.

Each member contributed distinct strengths, and the project’s success came from the way those strengths combined, blending different ways of thinking into something richer than any single approach could have achieved. Iteration was a key part of the development project. With each new version of the app, the team reflected on the quality of the prompts and challenges with the app to guide their next steps. Weekly feedback was the backbone of our journey.

Why It Matters

The apps developed through this project are not just educational tools; they are bridges.They connect disciplines that too often remain separate. They offer a new way for writers, students, and creatives to interact with data not as distant observers, but as engaged participants.

Each app is designed to spark reflection and narrative:

- A deer’s quiet movement across familiar landscapes.

- Sightings of great white sharks shifting across oceans and decades.

- The diversity of life flourishing across America’s national parks.

Already piloted with campus writing groups, the apps have demonstrated how a single dataset can inspire endless variations of story, poem, or reflection. That is the power at the heart of the project: one dataset, infinite perspectives.

Final Reflections

This project stands as a testament to the possibilities that emerge when disciplines meet—when data science, storytelling, and environmental engagement come together with a shared purpose. It reflects not only technical growth, but also a commitment to making complex tools accessible, beautiful, and deeply human.

The team expresses deep gratitude to the Dominguez Center for Data Science for supporting the project and to Kelly McConville for her encouragement, trust, and guidance throughout the journey.

As these apps continue to be shared and used, our hope is simple: that they will inspire others to see the stories waiting beneath the surface of every dataset—and to bring those stories to life.